Just like when David Cronenberg made a movie out of Naked Lunch, back in 1991, the arrival of Luca Guadagnino’s Queer, based on William Burroughs’ second novel, has caused considerable interest and nudged new generations towards discovering why Burroughs was a seminal figure in 20th century drug culture and counterculture generally.

Doubtless this has a lot to do with the casting of Daniel Craig as ‘William Lee’, the Burroughs alter ego figure, who looks absolutely nothing like Burroughs and isn’t gay – yet he carves out a persuasive performance using a limited, almost schematic repertoire of Burroughs’ characteristics: his oddball outsider status, his alienated nature and vulnerability, and his tendency toward intoxicated madcap performance.

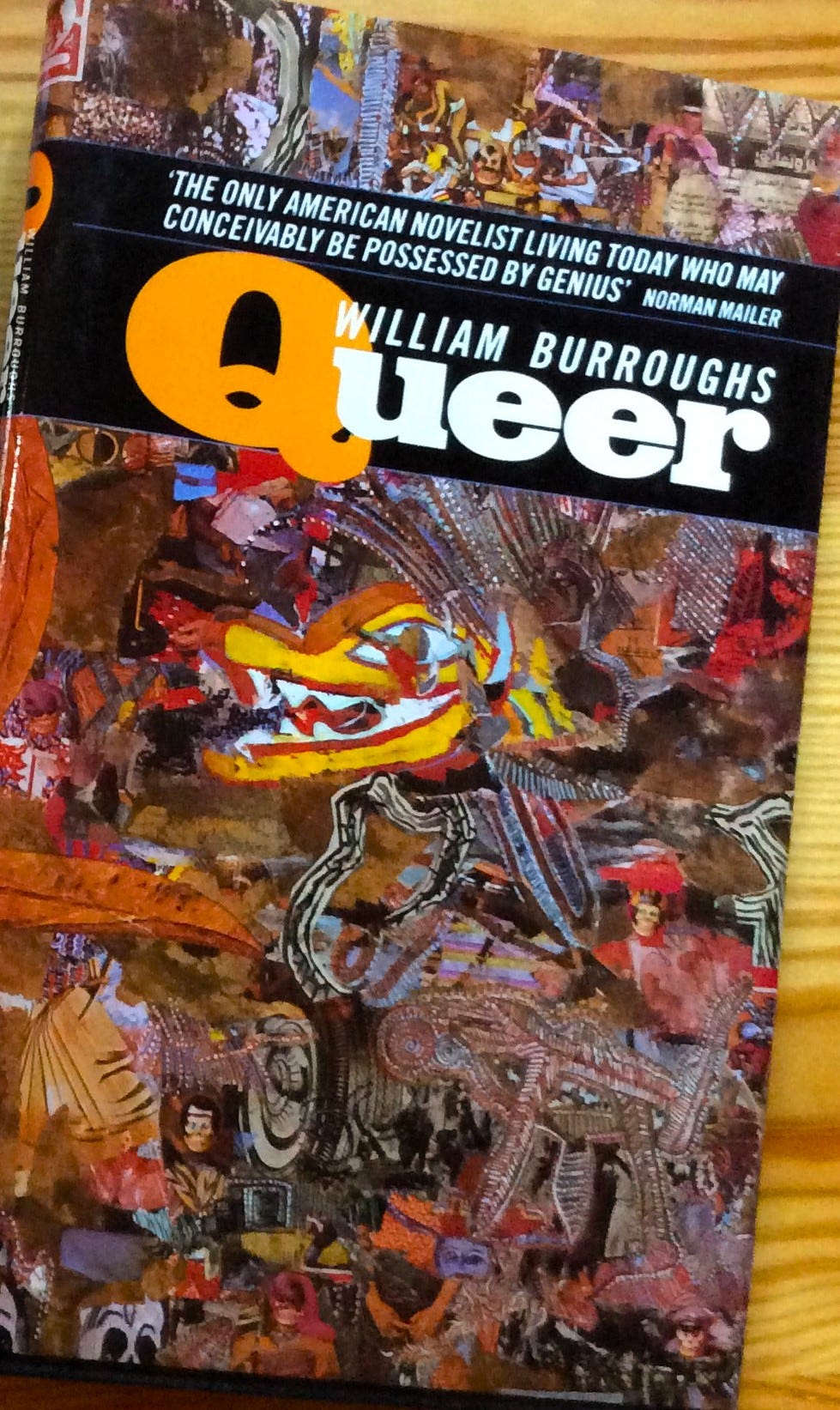

Using graphic one-word 1950s pulp fiction titling, the novel Queer follows Junky in promising a grubby, transgressive ride through a vice-laden underworld whose book cover readers might spy from a distance on a newsstand and purchase for prurient indulgence later. With Junky, this formula largely worked, but Queer remained unpublished till 1985, when Burroughs got a second wind facilitated by mythical agent Andrew Wylie (the Jackal), and his stock began to rise, leading to Ted Morgan’s excellent biography, Literary Outlaw, and Cronenberg’s film.

As much as the story itself, Burroughs’ new introduction to Queer, putting it in context, caused great interest. He cites it as representing a key intermediate phase between the factuality of Junky and the freeform experimental prose of Naked Lunch, showing alter ego Lee as the liminal ‘author’ of Naked Lunch, actually performing his outrageous routines to an audience, rather than merely writing them down – and that audience was his lover, Eugene Allerton, real name Lewis Marker (Drew Starkey).

Burroughs states that he was off junk when the real events of Queer took place, and therefore in a state of withdrawal, his emotions and impulses spilling out in a chaotic way and his sex drive acutely heightened. He was also undergoing a quest for creative identity and the two things fused together into his obsessive fixation on the Marker / Allerton figure.

The movie gets the flavour of all of this without spelling it out clearly. There is the gay bar banter at the Ship Ahoy, including the Joe Guidry (Jason Schwartzman) funny story about one of his pickups writing ‘El Puto Gringo’ on his window and Lee laughing, plus a comical origin-story concerning Lee’s homosexuality. But there is nothing of the routines themselves, with Burroughs’ classic outlandish imagery and surreal cause-and-effect. This seems a pity to me, as it would have clearly distinguished Queer as a specifically Burroughsian tale and not just another one about gay romance.

One of the best scenes in Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch has Lee (Peter Weller) deliver the famed ‘talking asshole’ routine as a verbal performance, which of course is highly suited to the medium of film. I’d have loved to have seen Daniel Craig do the same for the ‘chess’ routine:

The classic Arab chess game was simply a sitting contest. When both contestants starved to death it was a stalemate […] Did you ever have the good fortune to see the Italian master Tetrazzini perform? […] He had corps of trained idiots who would rush in at a given signal and eat all the pieces.

Or ‘Corn Hole Gus’s Used-Slave Lot’ routine:

Ten miles out of Tanhajaro, Abdul came down with the rinderpest and I had to leave him there to die. Hated to do it, but there was no other way. Lost his looks completely, you understand.

I note the chapter and verse of Burroughs’ highly un-PC gay humour, fully verbalised, may have landed uneasily with the audiences of today.

The cinema scene, where Lee and Allerton go to see Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus, is included, alongside the protean surreal imagery that the film invoked in Burroughs:

Lee could feel his body pull towards Allerton, an amoeboid protoplasmic projection, straining with blind worm hunger to enter the other’s body, to breathe with his lungs, see with his eyes. Learn the feel of his viscera and genitals.

Visually, this is put across as limbs reaching out, superimposed and crisscrossing. When the couple travel to South America and take ayahuasca, similar body-melding imagery is employed, fulfilling Lee’s impossible desire in hallucinatory form.

Of course Queer, the movie, wants to exist as a unified whole rather than as the second instalment in a series about William Lee, and Craig’s casting together with the emphasis on the ‘fiction’ in the work, renders this aim reasonably – if not completely – successfully.

Craig’s performance, which effectively captures nuances and ambivalence in Lee as a ‘gay character’, will probably win awards, and audiences will make their judgements on what the film is about, without the full information on Lee as a developing protagonist, including his subsequent role as the narrator of Naked Lunch, not to mention the cut-up trilogy and beyond.

Many people thought Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch was an actual representation of the novel, and not a mash-up montage of many Burroughsian sources, including ‘Exterminator!’ and Literary Outlaw. This kind of postmodern obfuscation, unique to Burroughs’s arcane universe, is part and parcel of the whole, and the man himself would have undoubtably liked Queer the movie…and be particularly approving of Daniel Craig.